SSL error. What now?

I think understanding SSL is one of those things that’s almost every IT professional’s to do list. Sure it encrypts stuff, but why then do you get those bothersome ‘self signed’ certificate failures that Chrome obviously hates.

Now, I’m not going to go into detail on how it works and how it works and how to set it up. I am just going to give you the highlights:

1. It’s all about certificates.

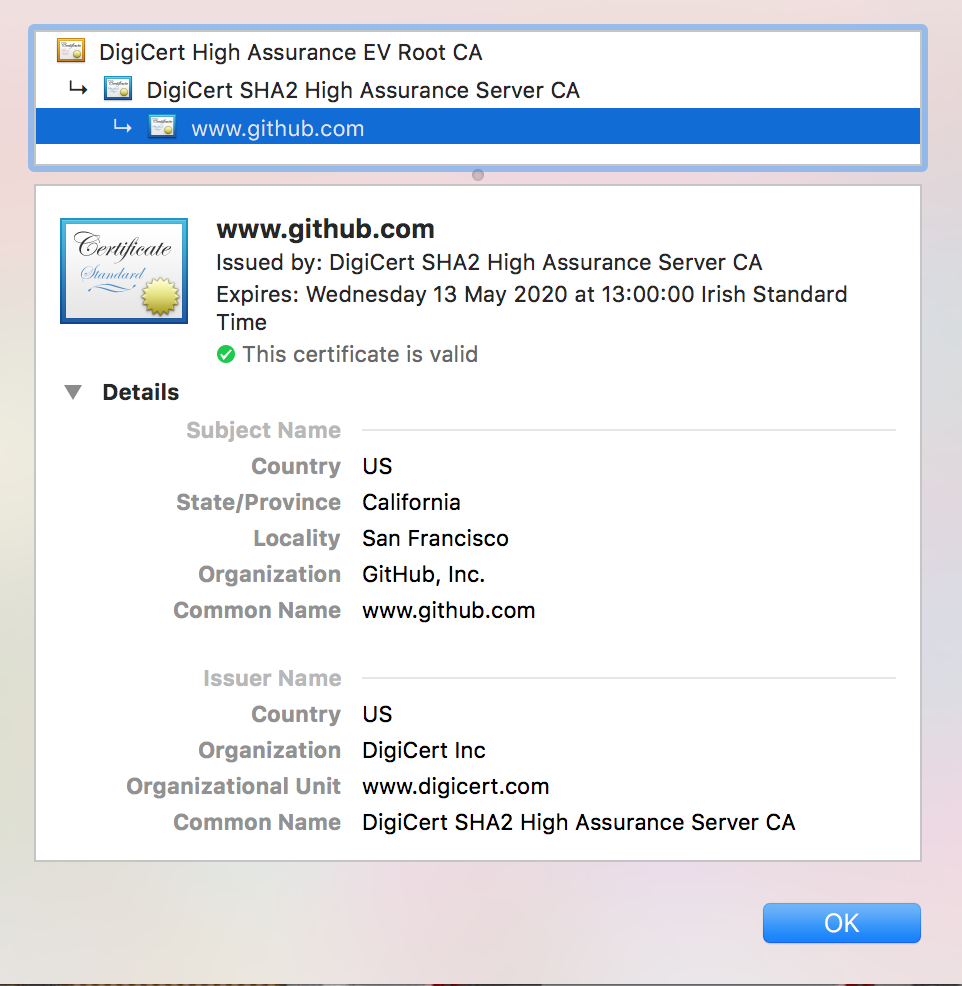

Certificates are a combination of a public key and some identifying information. See the figure below.

There are private keys too. There’s a private key that you get when you generate your public key. The other important private key is the one used by the Certificate Authority (CA). That is a VERY important key as it forms the basis of the chain of trust that is the foundation of how SSL works. More about that later.

Github’s certificate.

Github’s certificate.

2. Certificates are on servers

They get downloaded by browsers. They serve two purposes: firstly they are used to encrypt the traffic they’re sending between themselves, and secondly they are used to verify that you are who you say you are.

- The encryption is not that interesting to me right now – it is handled nicely by the server and the client and it very rarely throws up issues.

- The verification step is more interesting because that’s the one that breaks all the time. The way this trust is achieved is by having your certificates signed by a third party that both the client and the server both trust.

The private key is NOT downloaded. It is private. Remember that – private keys are like passwords – they’re PRIVATE.

Public Key: in your cert.

3. Certificates are ‘signed’.

Signing means hashing your certificate and encrypting it with private key of the signer. Using the signer’s public key allows anyone to decrypt the signature and compare it with the hash of the certificate. This allows people who don’t know you to trust your identity (provided they trust the CA).

A certificate’s signature.

4. The signer’s keys are well known

The signer, or Certificate Authority (CA), makes their public keys available, and browsers and distro makers build some of these well known CA public keys into their systems, which allows them to ‘Out of the Box’ verify any site signed by those CAs.

These certs are baked into MacOS

5. Who are the CA’s?

What does it take to become one of those well known CA’s? Not 100% sure. Probably money. Cue the conspiracy theory.

6. Signing requests.

When you want to host a website with ssl, you have to create a ‘Signing request’, which is basically the public key an identifying information. A CA then signs your signing request and BAZINGA, the resulting combination of information is a certificate.

8. Certificates come in chains

The one at the very beginning being the Root Cert. The smallest possible chain is 1, but that is the definition self signed, and Chrome don’t like that. The smallest useful chain is 2, as this allows you to sign lots of certs off a root cert + private key. In this case you only have to install 1 cert onto all your clients in order for them to trust all the certs that you sign.

More useful chains are 3 or 4 certs deep. This allows you to keep your root cert and key safe, and the intermediate certs can be used and revoked without making a load of changes to your clients.

Now, it’s a lot more complicated than that, but that’s the basic gist.

Some useful internet resources that helped me along the way:

- This video goes into a lot of detail explaining how certificates are put together, how the private key/ public key thing works, and how the whole lifecycle of the certificate chain works.

- Here is a nice guide on how to use open ssl to set up a key chain. Good first principles stuff.

Once you understand those two things, the FreeNAS CA screens will make a lot more sense

There is also another rabbit hole that I can go down about how CA’s (certificate authorities) are a single point of failure for the internet, and what’s more they are commercial interests, and we all know how trustworthy big companies are if they’re motivated by money. Money keeps us all honest after all.

That last bit was sarcasm for anyone who’s not paying attention.

Why did we just sit through all of that?

Anyway, moving swiftly on. Why do I care about SSL? Secure sites ( sites that start with https) much like domain names are theme that recurs a lot when you’re evaluating software and trying to set up services in your own home. Back on my second post, I ranted and raved about how I got stuck in an Ubuntu Landscape rabbit hole and had to eventually give up, because landscape’s web server did not have an http only endpoint.

Now, I understand that why that is. Every web application that is destined for any kind of production grade use should use SSL. It’s madness to send around credentials and headers and other other identifing information in the clear. So it makes perfect sense that Ubuntu would have an SSL option for their self hosted PPA. And given that it’s probably the same code that they use for their cloud service, it makes sense to discover it that it’s setup to be production ready it’s installed.

It just means that when you’re like me, a humble home user, and you just want to install something to see what it looks like, for research purposes, for home use or to be technology advocate in your day job, you begin to dread that ‘self signed’ certificate warning page. It’s not so bad in a browser – if you click the right buttons and if you’re lucky you land up on the desired page and the worst thing you have to contend with is some redness from the browser complaining about how the site isn’t safe.

But when your client is not a browser, but say a python script or a java program or some other piece of code buried inside a ‘product’, then it’s hard to ignore the certificate verification issues. Every program or library has their own way of handling the ssl error, and no two are the same. Some programs might not even provide a way to ignore certificate errors e.g. the landscape client. At this point, the easiest most straight forward way to overcome these problems is to use a proper certificate either by getting one signed by a well known CA or by setting up your own CA chain.

All you can eat ssl.

Now, the latter is ok these days. I started this certificate journey assuming I could just go and register a couple of certs with lets encrypt and I’d be sorted. But this doesn’t work well for applications that aren’t available on the internet because the CA will generally want to verify that you own the domain that you’re getting a certificate for. And to do this you either need to add a special file to your web server or perform some DNS magic. Neither of those are an option for something that isn’t visible to the CA’s infrastructure.

So that leaves us with setting up our own CA chain. And that’s where I’m going to leave it for this post. In the next post we’ll look into what FreeNAS gives us to help solve this problem.

Laters.